All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

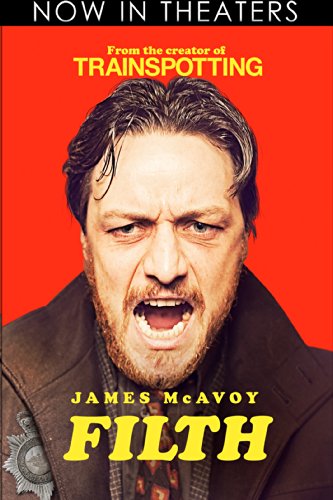

Filth

Like a ballistic knife straight to the heart, Jon S. Baird’s (Cass) adaptation of Irvine Welsh’s stream-of-conscious novel is a visceral cinematic sucker punch engineered to provide detailed character study through the most energetically portrayed lewdness to be depicted on screen since Martin Scorsese’s unlikely Christmas hit The Wolf of Wall Street. Aside from content, the two films share a similar attitude regarding their hypothetically unlikeable protagonists. Both warp the audience’s perception of the protagonist to see him as an anti-hero rather an antagonist through dynamic displays of debauchery. However, unlike Scorsese, who allowed Jordan Belfort the luxury of having a supporting cast of mostly loyal friends, the proposed anti-hero of Filth is isolated and alone in his self-indulgence, and has a nastiness to his being that’s impossible to shake. While The Wolf of Wall Street permitted audience members to view the film as a possible wish-fulfillment fantasy, Baird commits to the ugliness by ballooning the anti-hero’s unpleasant psychosis to such extremes that he could be committed himself.

What’s interesting about the film is that it isn’t fueled by the adrenaline soaked editing, spontaneous musical accompaniment, unexpected kinkiness, and potent profanity that would hypothetically define it. Instead, it’s James McAvoy’s central performance as the bipolar, bigoted junkie cop at the film’s twisted black heart that keeps the it engaging over 97 minutes of indulgent depravity. While the content is definitely questionable, there isn’t a gasp worthy or truly shocking moment over the course of the film. The mostly cartoonish supporting cast exists primarily to be inevitably humiliated, and the theoretically boundary pushing material stops being intriguing by the second scene of a naive woman being sexually harassed via telephone for dark comedy.

It’s James McAvoy who keeps the cartoonish tendencies of the plot in check with a deranged performance capable of bridging the gap between fast-paced caricature sadism and the consequences of devastating mental illness and unhampered trauma. Baird’s adaptation requires us to partially excuse the anti-hero’s actions due to his inherent insanity; an affliction stemming from the loss of his brother in childhood and the recent abandonment of his wife and daughter. However, this is a difficult proposition only made worse by a later development regarding a mysterious white-wigged woman. Even the aspects of the film designed to humanize characters eventually become bogged down in visceral cartoon logic and plotting, but McAvoy is more than capable of finding the humanity in the Tex Avery pseudo-protagonist. McAvoy is almost flawless; transforming a manic pitch black comedy into a searing character study. McAvoy takes every scenario thrown at his character with aplomb, and uses them to further flesh out “Bruce” in mannerisms and deliveries unlikely present in the screenplay. He becomes the glitter glue that not only holds the picture together, but makes it shine amongst similar films.

Comparing Filth to The Wolf of Wall Street might make for an unflattering and unfair comparison, but both follow a similar track: Character study through debauchery. While Filth approaches the material from a much more surreal and cruel perspective, it offers up many similar moments: Detours to strip clubs, over-the-top sex scenes, copious amounts of white powder. The crucial difference is that Filth fails to acknowledge its characters as little more than cartoons. Aside from Imogen Poots and Jamie Bell’s brief portrayals of fellow officers, every supporting character is either a caricature or broadly defined inevitable victim. The film also features the sin of casting Jim Broadbent as a psychologist, but relegating his entire role to delivering surreal monologues about tapeworms. While this may all be content derived from Irvine Welsh’s source material, without James McAvoy’s strong central performance, the entire picture would collapse after 20 minutes.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 0 comments.