All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

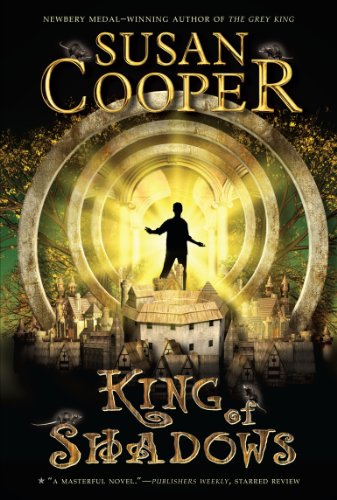

King of Shadows by Susan Cooper

If you’ve never met Will Shakespeare, do so immediately. Susan Cooper’s thin novel, “King of Shadows,” is a perfect place to start. In fewer than 200 exquisite pages, you’ll get to know the Bard intimately as you travel through time with your narrator, Nat Field.

Nat is a 12-year-old orphan who hides from his own brokenness by acting, mainly in Shakespeare plays and mainly well. He is recruited to play Puck by the exclusive Company of Boys, which travels from the United States to England to perform “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” and “Julius Caesar” in the newly rebuilt Globe Theater, a replica of the one in which Shakespeare acted 400 years prior. Shortly after arriving in England, Nat crosses that 400-year gap, waking up one morning to find himself in the Elizabethan era, expected to be Puck in “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” with Will Shakespeare himself playing Puck’s master, Oberon.

I suppose it’s no spoiler that the story ends as most accounts of time travel do, with Nat back in his own time. The unusual part is just how deeply Cooper immerses her readers into Elizabethan England first, with all its chaos and peculiarities. There are heads on pikes outside the Tower of London and bear fights in sketchy basements; chamber pots are emptied out of windows and beer is consumed at all hours because the water is contaminated. Sensitive, pre-adolescent Nat is often properly shocked. Yet, somehow, the London to which Cooper brings us is not only grimy and lawless but also vibrant and alive, full of street vendors, jugglers, acrobats, and freelancing bodyguards called “linkmen.” The historical details don’t read like a lecture but rather like the observations of a bewildered, somewhat naïve traveler, fitting perfectly with Nat’s overwhelmed, perpetually reactionary narrative voice.

In both of the story’s eras, the theater is a world unto itself. Anyone who’s ever acted will recognize the bustle of backstage, the tension of the first off-book rehearsals, the squabbles over blocking, the nerves of the first moments onstage, and the comfort of a well-rehearsed scene. Shakespeare’s Globe is even more hectic than the modern one, performing up to five different plays per week with the same overworked actors, but the costuming is amazingly ethereal and the audiences are vocally involved and emotionally invested in the plays. Nat’s experience there is thus both terrifying and magical, and the chapters set in the Old Globe will become favorites, leaving readers grinning and gasping by turns and always rooting for Nat. Those who have given up acting may even be tempted to pick it back up in hopes of finding a place and company as fantastic and homey as those of either of Nat’s Globes.

Believable characters populate both Globes and times. In the modern era, Arby stands out immediately as a talented, self-assured, bellowing force of nature—in other words, a director. Gil Warmun and Rachel Levin belong to a rare but not unheard-of breed of young adults who refuse to use their enormous talent as an excuse for snobbery and instead care for the younger and shier members of their social circles; Eric is the shy little kid who latches on to whoever’s closest. Meanwhile, those at the Old Globe are surprisingly familiar as well, subtly highlighting the basic universality of personalities both nice and nasty. Harry is your typical fair-weather friend, Roper is a bully, Will Kemp is a hotheaded artist, and Sam is the responsible older kid.

And Will Shakespeare. To Cooper’s great credit, she doesn’t allow her illustrious guest star to monopolize what is really Nat’s novel. Yet she spares no expense in fleshing him out, either: Will Shakespeare is real and alive and gentle and irritable and ridiculous and absentminded and brilliant and present, every time he steps onto the page. Readers who fancy themselves familiar with Shakespeare—who have researched him or already read his plays—may have trouble with the man Cooper calls Will: Though her research is clearly thorough, there are conflicting views about who Shakespeare was, and Cooper exercises her license as an author to cherry-pick which ideas to use. Readers as of yet unacquainted with the Bard, on the other hand, will have no such scholarly reservations about his characterization and will be hard-pressed to avoid falling in love with the brave, humble man who greets Nat as an equal.

Ultimately, far more than all the historical accuracy and familiar characters, Nat is the reason that “King of Shadows” is so compelling. He’s young and vulnerable and scarred enough to be an instantly sympathetic character, reactionary enough to force the reader to acknowledge the sometimes horrific realities of Elizabethan England, yet clear-headed enough to keep telling the story even at its grimmest points. Initially, traveling back in time seems to only aggravate the scars of Nat’s past. That’s why it’s such a revelation when the entire book turns out to be a story of healing—specifically, the way in which Will Shakespeare becomes a father figure for the still-grieving, fatherless Nat and teaches Nat enough about love that Nat’s world doesn’t fall apart when Will Shakespeare drops out of it just as suddenly as his father did. In a few short, beautiful, tearjerker scenes, Nat is flayed emotionally and forced to put himself back together. His success is simultaneously triumphant and heartbreaking, and its beauty and deep humanity are why I have read “King of Shadows” seven times.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 0 comments.