All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

Shackles: The Mystery of Standard Answers

“Zi yue: xue er shi xi zhi, bu yi yue hu.”

“Zi yue: san ren xing, bi you wo shi yan.”

“......”

The classroom teemed with sound of my fellow classmates reading ancient Chinese Classics. Everyone was reading out loud, well, except me. I was once again playing with my fingers and the last bit of my consciousness as a student flowed to the middle of nowhere. Losing my mind in the stream of recollection, I remembered those good old days when I could enjoy the pure beauty of Chinese Classics without answering questions on rhetoric and interpretation. I used to love reading Chinese Classics. But ever since the beginning of junior high school, I’ve been questioning my interest in Chinese Classics. Time climbed sluggishly when it came to Chinese classes in which teachers lectured on traditional Chinese Classics and bombarded us with a series of questions regarding those texts. What I would normally do, instead of jotting down notes as other classmates did, was to kill time by drawing caricatures of historical figures in the margins of the textbook, reading my own little novels, and, as I’ve already mentioned above, playing with my fingers. If Chinese classes are suffering, then Chinese Classics kill.

“Yutong.” Mrs. Sun, my Chinese teacher called my name. No response.

“Yutong.” Mrs. Sun raised her voice, but I was still busy playing with my fingers.

“Huang Yutong!”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“This is your fifth time today not focusing on the texts!”

My blatant non-response finally seemed to provoke her to anger. Abruptly, I held up my head with my forehead almost crashing with Mrs. Sun’s chin. Her stiff face amplified right in front of me like an image of a three-times magnifier, capturing a majority of my eyesight. Fury was all I could tell from her face.

Mrs. Sun wore glasses and always tucked her hair in a neat and tidy way, with the glasses sometimes reflecting one or two flashes. She was also an extremely erudite teacher prestigious for her profession of Chinese classics such as Si shu wu jing, not to mention Lunyu and San Zi Jing. Any student who encountered her at school would respectfully address her as “Mister,” meanwhile taking an exact 90-degree bow with infinite reverence and admiration, as if she were some kind of omnipotent god who was able to bless students with surpassing grades. Sometimes even her colleagues would do the same. Don’t get me wrong on this - my teacher was a “she.” In ancient China, “Mr.” was an honored title for any learned scholar who was respected and regarded by commoners as ones with higher social status.

“Tell me, then,” Mrs. Sun backed out a few steps, chest out, with her characteristic self-assurance of her own erudition on traditional Chinese culture, “what does this quote reveal about Confucius? The one that says ‘In bitter cold, we could see nothing other than bamboo and plum blossoms flower.’” Ah, another typical rhetorical analysis question. Students were required to answer a few questions on rhetoric, and this was one of them, asking students to analyze the underlying meaning of certain quotes.

“Uh...Uh... It... Uh no, they... They tell us that... The quotes discuss about plants in the wild like bamboo and plum blossoms so therefore it can be concluded that Confucius was born inquisitive and liked going into the wild to observe nature?” After a long and arduous “meditation,” I finally came up with something arguable (well, at least it seemed reasonable to me). But the whole class burst into laughter with me blushing and feeling as if I was the most foolish person ever.

“This quote shows that Confucius was trying to convey his lofty political aspiration that resembled the fragrant plum blossoms and his personal integrity that resembled the straightness of bamboos through the description of them not bowing towards storms and snow. I told you to memorize the standard answer so that you could get a good grade on the exams.”

“How could you not even know this?” Mr. Sun frowned with disapproval.

Ridiculous, inscrutable, arcane. Total nonsense and absolute absurdity. How ever possible could I know exactly what he thought? All I could do was to guess. For me, facing those questions was just like a native English speaker looking for clues for rhetorical questions of Shakespeare’s works. I never understood why students were required to answer such questions on rhetoric. Before junior high school, I actually enjoyed reading Chinese Classics and would recite some of my favorite quotes, except that my eager to read Classics could no longer last whenever I was to answer questions on rhetoric. Compendious and brief, Chinese Classics convey a sense of accuracy that no other languages dealing with modern grammar can ever achieve, yet the beauty that lies beneath words and phrases, the gracefulness that goes along rhythms and rhymes, are something not negligible as well. With just one word, Chinese Classics are probably able to deliver a meaning of a thousand words written in English, accurately and beautifully. What I really appreciate about the language of Chinese Classics, is its succinct elegance, is how it conveys ideas in such an effective way, but not the “SOAPSTone” or the “rhetorical appeals,” like the one Mrs. Sun asked me. More frankly, though, is that such open questions have the so-called “standard keys.” Although labeled “standard,” they actually restrict and limit students’ minds. How do we know exactly what Confucius think? Perhaps Confucius was a curious old man who kept telling students his adventurous excursions in class and the “experts” who compile the “standard answers” over-interpreted and thus distorted what Confucius really meant. Shackles and fetters would be a more adequate description of such “standard answers.” When teachers are crossing out everything that is not the “standard answers,” they are also eradicating students’ imaginative thoughts. Teachers at school, afterall, don’t care about the utility of such questions. Instead, they bear in mind the reputation and glory and pride of the school when students score high in the “National Gaokao” (the nation-wide University Entry exam in China).

Flames were burning in Mrs. Sun’s eyes as she slowly stressed on each syllable; both sides of her nose seemed to be twitching, and she was breathing so heavily that I could clearly see the ups and downs of her chest, then her whole face went petrified. She was obviously doing her best to palliate the fury, which I found quite amusing and did actually chuckle a little bit - which further irritated her. She waved me down, lamenting that I was deplorable and just as incorrigible as the moribund wood (as the Chinese old saying goes). And the next thing I knew was that I was made to stand for the rest of the class at the back of the classroom. Alone at the corner, with my heart filled with ignominy, I had silently smoothened out the pleats on the clothes and had flipped my eyeballs upward quite a few times before Mrs. Sun told me to mind my manner. However, I never really know why Mrs. Sun did not slap me in my face with the textbook (which my Chinese teacher at the elementary school did). She was clearly about to do so - I could tell by the way she suppressed her hand holding textbook. But I guess it’s because she was merely trying to maintain her scholarly pride and be as lofty as the plum blossoms, and did not want to be called “tyranny”, as some other teachers were criticized.

The same experience continued to haunt me and the humiliating scores of 70s in Chinese kept me skeptical and conscious of my ability to study well. Nonetheless, however hard I tried, during my time in junior high school as I was striving so hard to figure out the “correct answers,” my answer was either too “inane” or it “completely deviated from the standard keys,” according to Mrs. Sun. Always. As time went by, it was inevitable for me to unconsciously go off from Chinese classes (and Chinese classes alone), neither was it impossible for me to regain interests in Chinese Classics. Learning Chinese Classics was an invincible obstacle that continuously annoyed me throughout my three-year junior high school life, and, as I realized, would always be a problem as long as I was in the Chinese educational system.

What have I done wrong? And if it is not my fault, what have Chinese Classics done wrong? Or is there someone else to blame?

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 0 comments.

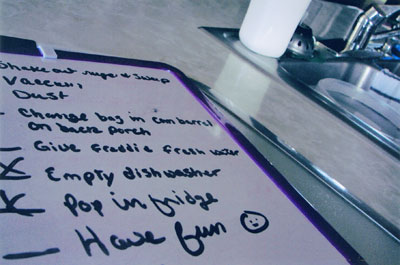

Some teachers at school sometimes impose the so-called "standard answers" to some open questions on students. They think this is beneficial to students by helping them score high; however, this, on the other hand, also constrained students' minds - just like shackles.