All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

Difficult

Routine wasn’t something I could rely on that year. In the middle of July, my dad interrupted a Law & Order: Special Victims Unit marathon to explain to my sister and I that he was moving out but it wasn’t our fault, he would still be our dad, he still loved us, etc. It was all said very carefully as if we were supposed to be shocked that the last few years of screaming had ended in divorce. At thirteen and nine, my sister and I were neither stupid nor deaf. Nothing about my dad packing a bag and a couple boxes and moving 1.9 miles away was noteworthy to us. People got divorced all the time, now it just happened to be our parents.

The next few months were court dates, yelling over phones, and scheduled weekend visits at my dad’s new apartment. My uncle visited a lot, but it was as my parents’ lawyer. My sister had to talk to her school’s nurse about how it all made her feel. My mom had to go to a doctor because she was sad. Everyone told me I was being very mature, such a good girl, so brave. I didn’t see what the big deal was.

By December they were officially divorced and everything settled back down just a little bit. Christmas passed as an awkward event split between parents, an unspoken competition to buy the best presents even though they were both broke.

In February, Grandma Lottie died in her retirement community in Virginia. I hadn’t known her very well because she lived in New Mexico before she was bullied into a condo designed for old people. We visited her for Thanksgiving the year before but the only things that stuck out were the community’s preference for fabric sunflowers and my dad’s endless joked at the expense of the elderly.

When she died, we got a call from my dad’s sister to explain Lottie had passed and that the funeral would be back in New Jersey. We played host to our distant relatives and my mom even went to the wake. For two nights, we stood around a room in the funeral home with more chairs than people and an open casket, the only topic for small talk being death and the family woes. Unfortunately, the biggest gossip was the tragedy of my parents’ divorce. Cousins I barely knew and people I had never met whispered and pointed at my sister and I. They were so sorry for our loss, but they weren’t talking about Grandma Lottie.

When May came around, everything had calmed down again. My grandpa was in the hospital for the fourth time in two years, but him being there was the closest I came to feeling normal. Pop Pop wasn’t like Lottie because he had lived in our house for as long as I had. He was the one who drove me to school every morning until my mom had to hide his keys because he was eighty and couldn’t read road signs anymore. He called me Honeybun and sat at the table with me when I did homework, offering to help even though he was terrible at math.

While my parents were learning how to be friends and my family was still grieving, Pop Pop was admitted to Palisade Medical Center, the hospital my mom had worked at for sixteen years, for renal failure. When my mom said it, she never sounded worried so I assumed it was nothing serious.

He’d been in the hospital for six weeks when my mom came up to my room to let me know she was going to visit him. She’d been there every day this month, half the time she was working and the other half she just went to see Pop Pop. “Daddy’s going to come over to make dinner later,” she said. “Kate’s in her room if you need anything.”

“Can I come?” I asked. She looked surprised that I was volunteering. The first week of Pop Pop’s hospital stay she had asked my sister and I if we wanted to come each time that she went. We both went the first couple of times and I went a few times without my sister. Eventually, my mom had stopped asking if we wanted to go. I hadn’t seen him in almost two weeks. “I want to bring him the statue.”

A week prior I had been at a yard sale, a dangerous place for a nine year old with a pocket full of quarters. I had gone under the pretense of getting some Mother’s Day presents: a puzzle of an all white cat with long fur and bright blue eyes that held the unnatural flash of a camera as the cat lay in a field of daisies, a teddy bear wearing a matching pink velvet vest and hat that was once securely attached to its head but now fell to one side, and an unfortunately painted moss green plaque with sloppily painted pink and orange flowers and an encouraging quote about home being the people you love or never really losing someone. On top of the Mother’s Day stuff, I found a ceramic statue. It was maybe a foot tall, an old man with white hair and ruby cheeks. One of his eyes was still a bright happy blue, but the other had faded to almost white. He had a fishing rod in one hand and a fish in the other, his smile echoing pride that was thrown off by his mismatched eyes. A red shirt and green overalls were as carefully painted and glazed as his face, but his shows had been left rough and chalky white. A rock at his face had the name Jack painted on it in the same red as his shirt. He looked a little like my grandpa and I thought it would brighten up his bleak hospital room. As far as I knew, he had never even been fishing but he had been in the Navy and that was as much of a connection as I needed.

My mom hesitated for just a moment before saying, “Yeah, of course. Hurry up and get your stuff.” I grabbed the statue and followed my mom out to the car. When I had shown it to her, my mom had liked the statue but mostly she was surprised I knew that people called Pop Pop Jack even though his name was John. I told her I didn’t even know his name was John, let alone Jack. I just liked the statue.

I was overly familiar with Palisades Medical Center. Not only had my mom been working there since before I was born, but my pediatrician’s office was the building just next door. More times that I care to remember, my mom had dragged me around the hospital after a doctor’s appointment so that I could meet all of her friends and coworkers. Meeting your parent’s friends was painful when perfectly healthy; it was hellish when you had strep throat.

We waved to Oscar the security, walked passed the gift shop with its flowers for condolences and balloons for congratulations, and got in the elevator. I knew the third floor was cardiac rehab where my mom hooked old people up to a dozen different machines and watched them run on a treadmill in order to fix their broken hearts. I knew the second floor was the emergency room where my mom used to work and I had met too many people to remember all of their names, where I had gone when I was six and slipped and fell in the bathroom. I knew the sixth floor was where Joanie, my mom’s friend from nursing school, worked in an office lined with filing cabinets. In the last month, I had gotten to know the fourth floor. Hospice was something else I didn’t understand. My mom used it when my dad asked about Pop Pop or when her sister called from Florida. The fourth floor was hospice.

When the elevator doors opened, my mom led the way to the nurses’ station where she talked quietly to Kathy Pinto, a nurse I knew because she bought Girl Scout cookies every year. My mom looked over Pop Pop’s chart even though she wasn’t supposed to and when she was satisfied we made our way to room 414. The door was closed so my mom knocked loudly and waited for a response. A nurse in blue scrubs answered, her forehead creased in frustration. When she saw my mom she relaxed a little and said, “Oh, hi Janice, how are you?”

“I’m fine,” my mom answered quickly. “How’s he doing today?”

“He’s being a little difficult this morning. Doesn’t want to take his pills, says he’s getting bedsores. We tried getting him up for a while but I don’t think that’s going to happen.” Difficult was a word frequently prescribed to my grandpa. Stubborn was another one. He ate his meals at exactly the same times each day: nine o’clock for breakfast, two for lunch, and seven thirty for dinner. If my mom took too long to make dinner, he wouldn’t eat because his movie came on Lifetime at eight. His routine was set and he was difficult.

My mom sighed and it was full of endless hospital visits and arguments she couldn’t win. She was bracing herself for something I still do not understand. She walked into the room and I followed close behind her, my arm wrapped around the fisherman statue. Pop Pop was sitting up in bed and his face was the palest I had ever seen. He was eighty-four years old and even though I cannot remember a time when he didn’t look old, these six weeks had age him too quickly. They had stopped shaving him because he was difficult about that too, so a scraggly white scruff adorned his face. His hospital gown hung off one shoulder and he looked all bones. The thing blankets and sheets were pulled up to his chest but he was still shivering. My mom was working on a hello when he cut her off shouting, “Get her out! I don’t want her in here!” I didn’t understand why he was yelling at my mom. She was a nurse and his daughter of course she should be there. “I don’t want her to see me like this! Get her out!” It took a gentle but firm hand on my shoulder before I understood he wasn’t yelling at my mom. He was yelling at me.

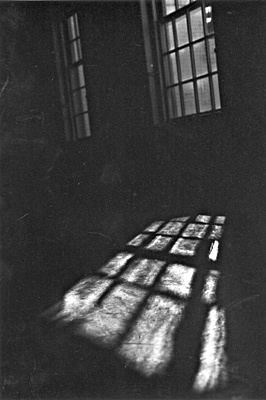

The other nurse led me to a chair out in the hall so I sat down. I still had the statue in my hands but now its singular blue eye looked aged and sad, its unpainted shoes looked sickly. The colors weren’t as bright and I felt stupid for having brought it. Hospitals were always going to be bleak and sad. You couldn’t cheer them up.

My mom didn’t stay much longer. The room had gotten quiet again once I left, but I assumed he was still upset. When she came back out she said, “Sorry about that. He’s just grumpy.” That was another word he got a lot. “Do you want me to bring that in there?” She pointed to the statue in my hands.

“Nah,” I said. “It’s not a big deal.” I wasn’t going to tell her that I was upset, that it hurt to see Pop Pop so upset when I was just trying to help. She had enough to worry about and I wasn’t going to add to that. I could handle his grumpiness, but I don’t think she could have handled my hurt feelings because she was too busy with her own. Despite my brave face, she looked sadder than I had seen her, even with all of the ups but mostly downs of the last year. For the first time, she looked worried and it occurred to me that maybe I was missing something. She grabbed my hand and we went back to the elevator. We didn’t make our usual rounds to say hi to all of her friends and let them fawn over how much I had grown. Instead, we made our way back to the car and drove home.

The next night my dad came over with pizzas and a movie while my mom went back to the hospital. He, my sister, and I were fully absorbed in the TV when his cell phone went off. “It’s Mommy,” he told us but we weren’t listening. When he got up to answer it, we didn’t look away from the TV. He was gone for a couple minutes and I heard him apologize a couple times but he only had a small amount of my attention. His footsteps were loud as he came back over. “Hey, Kate, Mommy wants to talk to you.” He handed her the phone and sat back down, ruffling my hair as he did. I finally broke away from the screen long enough to glare at him but his face didn’t look right so I froze. I had seen my dad sad, angry, and just plain upset, but I had never seen him serious before. I listened to my sister’s side of the conversation but all I got was “Sure, here she is,” before the phone was being handed to me.

“Hello?”

“Hey, Jack,” my mom replied. Her voice was grainy like mine when I first wake up. She cleared her throat. “So, I don’t know how to tell you. But, well, you see. The thing is.” The words were fighting back. Nothing sounded right to her and it certainly didn’t sound right to me.

“What’s the matter?” I asked. I think I already knew the answer at that point. Yesterday had been upsetting for the both of us but we never talked about why.

“Pop Pop passed away a little while ago. I’m really sorry, but you know how sick he’s been.” The problem was I hadn’t really known. He’d been in the hospital so many times but he always came home eventually. I never thought this time would be for good. I didn’t know that renal failure meant his kidneys had stopped working, that the rest of his body would follow in a similar patter until pneumonia set in and there was nothing left of him to fight back. It didn’t occur to me that my mom the nurse would treat death differently, that she would see it coming and be ready. Nobody stopped to explain it to me, nobody warned me because I had already experienced the loss of a grandparent and I had survived the divorce. People had a habit of handing me difficult things and looking away before they could see me struggle. Or maybe I was just hid it too well.

At eighteen, nine years after Pop Pop’s death, I went away to college and the jokes about having a crazy roommate were manifested in Sarah, a sophomore neuroscience student who just wanted to be a musician. The first month was easy enough but October was four weeks of Sarah’s frequent partying and disappearing acts. Eventually, she stopped sleeping all together and ran on nothing but bursts of creativity and weed. Art projects made from empty Kool-Aid packets and expired coupons were replaced with days stuck in bed, skipping classes and meals.

I did all I could to convince her to talk to someone, but the anger was only slightly less biting than her sadness. I didn’t want to bother anyone else with the problems I seemed to have adopted when Sarah and I started living together. When there were no other options, I explained it all to our RA, an invasion of privacy that would have made Sarah snap had she ever found out about. I was commended for handling it so well. A similar episode from the previous January was discussed as though I knew Sarah had broken away from reality and been sent home for four week. I didn’t know about Sarah’s history with depression. No one knew she had been misdiagnosed and being bipolar was entirely different from just being depressed. When she disappeared for five hours on a Thursday night, I wandered campus with the RA and the head of Residence Life until we finally found her sitting in a magnolia tree. A phone call to her mom later and she was leaving school for the rest of the year.

At five in the morning, I lay in my bed confused and frustrated and homesick because when you fill out a roommate questionnaire they ask about sleeping habits and cleanliness but never if you’re expecting a mental breakdown in the near future. To everyone else, it was fine because I was the one who was always calm and never stressed. I could juggle Sarah’s illness and my first year of college all while being five hundred miles from home without a problem. In the dark just after she left, the strangely vacant left half of our room and the way I couldn’t stop crying spoke to something entirely different, but I couldn’t find it in me to correct any of them. I had survived the crazy roommate the same way I survived the loss of two grandparents and a divorce in a single year. Survival doesn’t mean any of it was easy.

My dad took the phone back when it was clear my mom had delivered her message. He promised to hang out until she got back and then hung up. When asked if we were okay, my sister and I gave identical, automatic nods. I looked at the dining room table, at the chair Pop Pop ate dinner in every night for as long as I could remember. The dark wood finish didn’t match the new dining set my mom had gotten because Pop Pop had decided the new chairs were too hard for him. The odd chair out was where he read his newspaper as he ate his Entenmanns crumb cake every morning, always slipping some to the dog that lounged at his feet. Where we played board games on Saturday afternoons and where he let me drink coffee with him when my mom was at work. He wouldn’t be coming back to that chair, wouldn’t be coming back home. For the first time, I could see why my mom always complained about the chair that didn’t match; it looked wrong.

The statue was on the table, just passed that chair, where I had left it after the previous day’s disaster. I thought about how it would get put in a box and moved to the basement to be forgotten and that was sadder than Pop Pop dying. I went to the table and picked it up before going upstairs to my room. I cleared a spot on my dresser for it and put it there. Knowing he wasn’t going to be forgotten about was a relief to me. His one blue eye still looked sad, but I liked having him there. I don’t understand why the poorly painted fisherman was the most comforting thing when things had finally been too much to keep making sense of it all.

All I knew then was that I had to go back downstairs and finish the movie because my mom would be home soon. When she finally got back, she asked if I was okay, so I hugged her and said I was fine. It didn’t really matter if I was actually fine because it was what she needed to hear. I would figure out whether it was true in my own time.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 0 comments.