All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

Copper

Cu.

Two imposing feet beat upon the sidewalk. With each rhythmic step, expensive pant legs undulate, mimicking the current of the wind that ushers the man forward. He reaches the awning, continues forward for a little while longer, and then stops. He adjusts his suit. He reaches into a silk lined pocket, withdraws a handful of change, and bends at the waist. The man bows down to the newspaper box and deposits the four quarters. Still bent, he withdraws a fresh, crisply folded newspaper, smelling of ink. Every day he does this on the way into work. It is a subconscious homage to a hopeful reality.

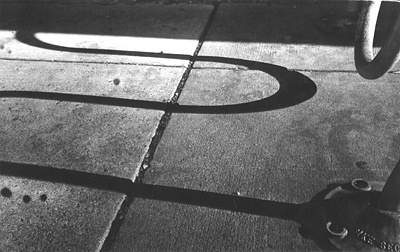

The man stands with his paper and begins walking away. He carelessly funnels the unused coins back into his pocket. They clink against one another reassuringly, except for one. A single penny spirals toward the earth. The copper doesn’t glint in the flat light—the color seems cool instead of warm and earthy. Abraham Lincoln twists in midair, head over heels. With an insubstantial ping, the penny lies still. The year 1994 faces a monotone sky. Two feet beat upon the sidewalk. Expensive pant legs retreat.

The warmth of the penny quickly leaches into the concrete. Cold and lifeless, the penny waits. Suns rise and fall, shoes pass by as 1994 watches. The penny is kicked. It collects dirt; the copper’s perfect sheen is mangled. Lonely, 1994 watches a constant trickle of currency fall into the newspaper box. 1979 goes in. 2001. A 2012 quarter, gleaming like it came straight from the mint, enters. No other coins fall nearby. The first man, its original keeper, bows, receives, and then walks away each day. The penny remembers that satin-lined pocket; it remembers the camaraderie of a piggy bank. The penny waits as women, children, and animals disregard it. 1994 is only a penny, after all.

Two grubby fingers approach. The cuticles are mangled and the nail beds are dirty. The shoes are not the expensive shoes of the penny’s last owner; instead, they are broken, dirty, and mismatched. The penny is lifted, examined, and at last, pocketed. This time, instead of falling into a silky cocoon, the penny finds itself inside a tiny ecosystem. Inside the pocket is an ant, a hard candy, and a crumpled scrap of paper. The ant tries to escape from the pocket, but fruitlessly: each time it scurries toward the light, it tumbles backward.

The penny walks with the man, feeling his stooped posture and uneven steps. The copper-plated eyes embossed on the penny’s surface see only darkness, but the ridges along its side rasp a description of the man’s gait. 94 doesn’t know where it’s going. A doorbell chimes and the temperature changes. The smell of coffee permeates the air. The man walks to the counter of the coffee shop. His voice grunts a request for a cup. He waits, and then walks out. Before long, the man sits against a wall, parking himself on the familiar texture of concrete.

Now, instead of on the ground, the penny lives in a cup. The man shakes it mercilessly whenever someone walks by, and sometimes, he is rewarded. Companions tumble inside; the penny is no longer alone.

1994 meets 1995. The two meet a 2003 dime. A 1949 quarter. In the mysterious language of coins, they converse. 2003 is jealous of 1949’s solid silver composition. Two copper Lincolns collide with a wall of Styrofoam, and then a disgruntled Washington. A quarter dollar from Delaware compares its design with Georgia’s. The penny becomes part of a turbulent, changing community. It becomes claustrophobic as coins pile inside.

A doorbell chimes again, this time more electronic sounding and lower in pitch. The grubby man and his equally grubby cup enter a fluorescently lit building. A few steps, and the penny and its compatriots are dumped onto a Formica counter. The coins slide against one another in a miniature avalanche, spreading in a puddle of metal. 1994 can breathe again. Different hands approach—clean, but calloused. The penny is separated and counted by the clerk. The dirtier of the two men makes his exchange, leaving with a package of cigarettes. The penny is left on the counter. The doorbell chimes again and a burst of cold air circulates as the man leaves, Styrofoam cup in hand.

The calloused hands cup 94 and others of its kind, and then gracelessly dump them into a cash register drawer. The air inside the register is musty and dank, but is refreshed often. The doorbell chimes. The penny is knocked against a sea of other coppers. 1994 lives in a community both more uniform and more tumultuous than the last. Members come and go, but 94 stays with an I don’t want the penny or You can keep the change. Again, the penny waits.

94 is used to hearing feet. A set of large and a set of small one approach the counter. One ninety-nine, says the clerk.

Two crisp singles enter the miniature bank as the penny leaves it.

The penny passes from the impersonal hand of the clerk to the hand of a mother. It knows the feeling of a wallet; it absorbs the warmth of a hand. The penny wedges itself into a corner of her change pocket, hoping to stay there. Blind, Lincoln hears the cap of a soda being twisted off. Blind, Lincoln hears the open and close of car doors and the click of a doorknob.

The mother empties her purse and opens her wallet. She unzips the pockets and methodically empties the coins into a jar on the kitchen counter. The penny likes this jar. 94 watches the workings of its new home, the interactions of father and mother and daughter. It sees life, laughter, and stress. It watches as the bills get paid and dinner cooked. It watches a young girl lose her first tooth in a candy bar, and it follows the tooth under the pillow.

The penny, a meager prize, stays with the girl. She puts it into her pocket and brings it to school to show her friends.

Find a penny, pick it up, and all day long, you’ll have good luck, the girl sings. She skips out of school and toward the bus. Predictably, the penny falls out of her skirt pocket.

1994 flips as it falls. It is oxidized and stained; it no longer shines. It hits the sidewalk with in insubstantial ping. Two feet retreat into the distance.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 0 comments.