All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

The Money Tree

The Money Tree

Anton Weber could not fall asleep on the first night after the move. He was twelve and the last six months of his life had been miserable. His parents had passed away and left his elder siblings, Benjamin and Beatrice, in charge. Soon after, they sold everything and moved to the small brick house miles from civilization. The bricks were dull red and dusty.

Anton nestled in his cramped cot, but sleep would not come. Beatrice breathed softly in the room next door, and Benjamin, who was the oldest, snored like a tank in the bed a few feet from his. Poor Benjamin was bundled up in a blanket, his graying head peeping out from the sheets. He was only twenty-five. It was a full moon.

Anton sat up in the moonlight. He kicked his blankets off and swung his legs out from the cot. Then he made his way downstairs where he got a drink of water and looked out the window.

There was nothing to see. But he thought he could hear a shuffling sound outside, so he ran back to his bed and fell asleep.

And woke up the next day. The sun was high and his siblings were already awake, cleaning and sweeping and hauling luggage. Anton laid in the patch of sunligh

t and stared up at the ceiling.

“. . . Anton, Anton,” Beatrice called. And Anton realized with a start that he had been dozing off.

“Stop sleeping, Anton,” snapped Beatrice. She put her hands on her hips and rolled her eyes. “Stop being so lazy all the time.”

Anton barely heard her. He was fantasizing about exploring.

“I’ve already put away all my things,” he said, “could I go outside?”

“all of your things?”

“Yes.”

Beatrice sighed, “alright, but only if you promise to sweep up the leaves in the backyard first.”

“I promise.”

Anton found his bicycle and a huge rusted rake among the pile of boxes and dragged both out through the kitchen door. After leaning his bicycle against the brick wall, he grabbed the rake on the top and the middle of the handle, and dragged it across the uneven grass. The prongs caught a few helpless leaves and trailed them in its grasp until other leaves joined them. Anton thought of it as a game to see how many leaves he could trap with one drag. If the leaves filled to cover the prongs, then he was winning, if he could see the forks, he lost.

Soon, there was a pile of leaves that came almost to his knees, and Anton was bored of the game.

The house was in the outskirts of a forest. The backyard was almost swallowed by the creeping trees. The branches were big and gnarled, their leaves dark blue and black. It was among such trees that Anton found a small foot trail. It was hidden by overgrown bushes that pricked his fingers, but the ground was packed dirt worn down by human feet.

Anton discarded his rake and followed the trail. It twisted and turned and spun, through vines and over roots, so busy and long that Anton soon lost track of time and direction.

A bird chirped somewhere from a tree, and an animal rustled leaves behind him. Anton was almost scared.

There was a smell wafting from ahead. At first it was hardly noticeable until suddenly it became unbearable, like rotten garbage and old food. Anton Weber followed the smell and the trail.

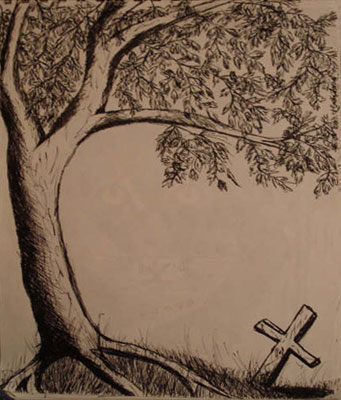

Which lead to a small clearing. The clearing was slighting hilly, with a young tree atop the slope. The sun was peaking through its bare branches. It looked as if it were dying.

Anton climbed the hill, which led to him discovering the corpses.

The air around them stank terribly. The corpses were overripe and Anton fell backwards, throwing up and throwing up again. His head was swarming from the smell, his empty stomach heaving until he was retching up green goo.

Somehow Anton was at the bottom of the hill, out of sight from the dead eyes, gasping and running on the foot path again. Branches grabbed at him, roots tangled his feet causing him to trip, and the rotten odor stalked him from behind. He wished for any trace of the red house among the green, and prayed as he stumbled blindly through the growth.

Soon Anton was out of breath, and he was back in sight of the small red house.

Beatrice was waiting for him by the kitchen door, her arms crossed and her foot tapping against the wooden floor. Gasping, Anton tried to tell her about the dead bodies in the woods, but Beatrice would hear nothing of it. She stubbornly shook her head and wordlessly handed him the rake he had abandoned to go exploring. And Anton had no choice but to meekly return to his task.

Throughout the day, the tree and the bodies on the hill stayed in his mind; he saw them in the leaves he was raking, in the folds of Beatrice’s dress as she bandaged his cuts and bruises, in the plates that he set at the table, in his soup during dinner. But they had taken on a surreal quality. Anton was not sure he had seen the bodies. Beatrice thought it was ridiculous, and maybe it was. Maybe they had been nothing more than a broken branch or an oddly-shaped rock, not actual corpses. Among the realities of the red brick house and his siblings, his discoveries in the wood seemed no more than a dream.

Anton Weber easily fell asleep that night. Which lead to a nightmare about the bodies underneath the tree. In his dreams, the corpses still had their faces. And the faces were his dead parents’.

And he woke up in the dark. In the dark, everything seemed more real. The forest was real, as well as the hill with the tree and the bodies. They were real. Anton thought of his dead parents. How would they have felt if they had been left out cold in the middle of a forest?

He didn’t have to go. And Anton did not want to leave his bed. But he found himself swinging his legs out from underneath the blankets. He stared down at his feet. They were pale like a bruise. He slipped them into his boots.

Anton grabbed his jacket from a peg and a lantern from his bedside and crept downstairs. He tiptoed across the dining room, across the kitchen, and eased open the door that lead to the back. It was pitch dark. Even when he shone the light directly outside, he could not make out more than few feet in front of him.

He should have been frightened. But Anton felt fearless. There was a hoot from somewhere in the darkness; further away, a howl. He ignored the ominous calls, and made his way to the shed next to the red brick house, where he found a shovel.

That night, Anton Weber buried the corpses underneath the tree.

Throughout the month, Anton frequently visited the tree. Benjamin and Beatrice were unbearable sometimes. No one could see or bother him in the woods, and he enjoyed watching the tree on the hill grow. It grew quickly. It had been a scrawny sickly thing, its branches bare and its trunk thin and yellow. Now, under Anton’s care, it seemed to shoot upwards at an alarming pace. The large rectangular rock that Anton had put over the graves was soon devoured by its roots, and the trunk grew so thick that he could not wrap his arms around it.

The branches that had been bare now were dotted with small green buds. Anton sometimes played around with them, peeling away the bud to see the leaf inside. Mostly he just sat by its roots or took a nap.

Benjamin was always too busy to notice, but Beatrice was becoming more annoyed at Anton’s periodic disappearances. She would assign him some chore, and as soon as she turned her back, he would disappear for hours at a time. She was worried for him; children Anton’s age should have friends, but no one else lived within miles of their little house. Beatrice worried he would grow up odd and alone.

When she confided in Benjamin one night, she found that he had the same concern. They were sitting at the dining room table, sorting through bills and papers, when this topic was raised. It was almost midnight and Anton was deeply asleep in his room. In the dead darkness surrounded by night noises, Anton’s disappearance into the woods seemed worrisome, almost dangerous. Which led to their decision to follow Anton the next day.

As it turned out, the next day marked the first time the tree’s leaves started to fully emerge from their buds. Anton Weber got the shock of his life when he navigated through the woods as usual--unaware that he was being followed by his siblings--and climbed the hill to find the tree peppered with crisp twenty-dollar bills.

Anton was prying a twenty-dollar bill from its petiole when Beatrice and Benjamin saw the tree. And fell speechless.

“Anton . . . what is it?” Beatrice asked. She picked up a twenty-dollar-bill leaf from the grass.

“It’s a money tree,” Anton replied.

“There is no such thing”

“There is so,” he argued. “This,” and he gave the tree a pat. Benjamin confirmed it by plucking a bill from the lower branches and examining it under the sunlight.

The three siblings felt better than they had in the last six months. When they returned to their red brick home, their pockets were stuffed with money. And the next day, they were able to buy back some of the belongings they had sold off before. Beatrice finally bought a new dress.

The day after, Benjamin and Anton returned to the money tree with large burlap sacks. They filled their almost to the brim, and stuffed their pockets too. With that, Benjamin bought some furniture and was able to repair the old shed next to their home.

Weeks passed, which led to flowers blooming on the money tree. The flowers were large and white. And they were government bonds. Benjamin took only a few, but harvested more of the leaves.

Only days later, the flowers became fertilized and swelled with the weight of their fruit. The government bond flowers slowly curled away, revealing the diamonds that had been nestled among the petals. The siblings waited until the first batch of diamond fruit ripened, and harvested them all. They hid them beneath the floors of the red brick house, and were worried people would notice. And then they waited fervently for the next batch of fruit to mature into suitable size.

However, the tree had lost some of its vigor, it seemed. It took almost a month for the next flowers to produce the diamond fruit, and when they did, the fruit seemed smaller and duller than the first batch had. Seeing that, Beatrice made them stop. Too much harvesting could hurt the tree, she said. They still went to the tree to gather some of the fallen money-leaves, but mostly they decided to leave the tree alone.

Meanwhile they put the diamonds to good use; Benjamin first purchased the forest behind their red brick home, then hired workers to put up a tall fence all around their estate and the woods. He used the money-leaves and profit from the diamonds to invest in the stock market, and his success earned even more money. Beatrice decided the little red house was too small for the three of them, so she had workers cut down a section of the forest and build a larger home next to their old one. Anton got himself a new bicycle and eventually, when he became older, a new car. They were almost happy.

The tree continued to produce the money and the diamond fruit, but more sparingly. Each flower took almost a year to bloom, and the diamonds began taking longer to ripen. It also seemed as if it were aging; the previously full branches and leaves were becoming more sparse and some money-leaves started to show a sickly yellow tinge. It was barely noticeable but the siblings worried.

They were older now. Anton Weber was a grown man, and the siblings had their own individual properties some distance away from the tree. They were all very successful. And they were all in disagreement.

Benjamin stressed that they did not need the tree; they could abandon it if they wished to. Anton wanted to harvest all they could from the money tree and leave it.

“It looks as if it’s going to die soon anyway,” Anton reasoned.

“How can we leave it? Other people might chance upon it, we should chop it down ourselves,” Beatrice argued. Beatrice tried to make Anton see her way but he was twenty-one, old enough to make his own mind. And so on went the arguments.

Then came the day a man trespassed onto their property and stumbled upon the money tree. Benjamin caught him trying to smuggle out a bagful of diamonds and shot him on sight. He dragged the body back to the tree, and called his siblings out to the hill.

Beatrice and Anton were very familiar with the track by now, and they arrived within a few minutes. When Anton saw the body underneath the tree, he was reminded of his first day. Beatrice burst in tears when she saw Benjamin and the body.

“The tree is dying, just leave it alone,” Beatrice cried. Benjamin tried to soothe her, then when it did not work, he tried yelling. Beatrice yelled back, and soon all three of them were screaming at each other.

“I can’t take this anymore,” Beatrice looked determined, “I’m going to tell the world about this money tree. It’s not ours.”

Then she grabbed a handful of diamonds and twenty-dollar bills from the tree, and turned towards the trail. Which led to Benjamin instinctively shooting her in the back. Beatrice died.

This time it was Anton who cried. Benjamin tried to soothe him, then tried to reason. No outsider should know about the tree, Benjamin said. If the world found out, wars would be fought to control the money tree. Anton didn’t care; he wrestled the weapon from Benjamin and shot him also. Benjamin died even more quickly than his sister had.

Anton Weber was twenty-two, and the last ten years of his life had been miserable. He had turned mean and paranoid, worried that people would find the money tree or the tree would wither away to leave his family with nothing. He lived in a large comfortable manor but he wished he could see the red brick house through the packed woods. He couldn’t. He hoped someone would come find the bodies and bury them, as he did all those years ago. Anton Weber shot himself and died also.

The siblings did not have any other family, so no one found their bodies for months. It was a group of friends that wandered into the forest one day. They were exploring when they smelled the terrible smell and found a withering tree on a hill with the corpses scattered about.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 0 comments.

Inspired by Kurt Vonnegut's "Slaughterhouse Five"